Mayumi Hosokura

Exhibition at TSCA

- Mayumi Hosokura | walking, diving 2 September - 21 October, 2023

- Shuhei Ise, Enrico Isamu Oyama, Mayumi Hosokura, Rafaël Rozendaal 16 April - 21 May, 2022

- The Eye Draws | Mayumi Hosokura 4 September - 23 October, 2021

- Digitalis or First-Person Camera | Umi Ishihara, Maiko Endo, Yokna Hasegawa, Mayumi Hosokura 17 April - 19 June, 2021

Profile |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Awards |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Solo Exhibitions |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Group Exhibition |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Publication |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Collection |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Others |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Profile

| Mayumi Hosokura | Lives in Tokyo and Kyoto. Mayumi Hosokura’s haptically visual photography and video works address the shifting boundaries between body and sexuality, human and artificial, and organic and inorganic materials. She studied literature at the University of Ritsumeikan and photography at the Nihon University College of Art. Major solo exhibitions include The Fluid Gesture (2025, ss space space, TW), walking, diving (2023, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo, JP), Sen to Me, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo (2021), NEW SKIN, Mumei, Tokyo (2019), Jubilee, nomad nomad, Hong Kong (2017), Cyalium, G/P gallery, Tokyo (2016), CRYSTAL LOVE STARLIGHT, G/P gallery, Tokyo (2014), and Transparency is the new mystery, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei (2012). Major group exhibitions include Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions 2023 Technology?, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo (2023), Post-Human Narratives—In the Name of Scientific Witchery, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, Hong Kong (2022), KYOTOGRAPHIE 2022, HOSOO GALLERY, Kyoto (2022), Digitalis or First-Person Camera | Umi Ishihara, Maiko Endo, Yokna Hasegawa, Mayumi Hosokura, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo (2021), The Body Electric, National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (2020), Things So Faint But Real: Contemporary Japanese Photography vol. 15, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo (2018), Close to the Edge: New Photography from Japan, Miyako Yoshinage, New York (2016), Tokyo International Photography Festival, Art Factory Jonanjima, Tokyo (2015), and Reflected – Works from the Foam Collection, Foam Amsterdam, Amsterdam (2014). Hosokura has published numerous photobooks, including WALKING, DIVING, artbeat publishers (2022), FASHON EYE KYOTO by MAYUMI HOSOKURA, LOUIS VUITTON (2021), NEW SKIN, MACK, 2022, Jubilee, artbeat publishers (2017), transparency is the new mystery, MACK (2016), FASHION EYE KYOTO by Mayumi Hosokura, LOUIS VUITTON (2021). Her work belongs to the public collection at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, among others. |

|---|

Awards

Solo Exhibitions

| 2025 | 曖昧な決定、肉、光, COPYCENTER GALLERY, Tokyo, Japan The Fluid Gesture, ss space space, Taiwan |

|---|---|

| 2024 | A house of bodies, OASIS 2, Kyoto, Japan |

| 2023 | walking, diving, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo |

| 2022 | I can (not) hear you powered by EDION, Kyoto Kawaramachi Garden 8F, Kyoto CELL(s), Sony Park Mini, Tokyo |

| 2021 | The Eye Draws, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo |

| 2019 | NEW SKIN, mumei, Tokyo |

| 2017 | JJuubbiilleeee, G/P gallery, Tokyo JUBILEE, nomad nomad studio, Hong Kong |

| 2016 | CYALIUM, G/P gallery, Tokyo |

| 2014 | CRYSTAL LOVE STARLIGHT, G/P gallery, Tokyo Transparency is the new mystery, POST, Tokyo |

| 2013 | Floaters, G/P gallery, Tokyo |

| 2012 | Transparency is the new mystery, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei KAZAN, Spiral Hall, Tokyo |

| 2011 | KAZAN, G/P gallery, Tokyo |

Group Exhibition

| 2025 | スープを散布する新婦とpimp, COPYCENTER GALLERY, Tokyo, Japan METAMORPHOSIS: Heinz Hajek-Halke & The New Image-Makers, CHAUSSEE 36 Photography, Berlin, Germany TOP Collection: transphysical, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo Japan |

|---|---|

| 2024 | TRANSCENDENCE, Vague Arles, Arles, France Concrete Island, Seasons, LA, USA |

| 2023 | TOKYO FASHION STRIDE 1st Stride, Shin-Marunouchi Building, Tokyo, Japan The Yebisu lnternational Festival for Art & Alternative Visions 2023 "technology?", Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo |

| 2022 | 50 seconds,Soda, Kyoto Shuhei Ise, Enrico Isamu Oyama, Mayumi Hosokura, Rafaël Rozendaal, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo 後人類敘事——以科學巫術之名 Post-Human Narratives—In the Name of Scientific Witchery, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Science,Hong Kong |

| 2021 | Post-Human Narratives−The Co-existing Land, Unit 12, Cattle Depot Artist Village, Hong Kong Digitalis or First-Person Camera | Umi Ishihara, Maiko Endo, Yokna Hasegawa, Mayumi Hosokura, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo Anneke Hymmen & Kumi Hiroi, Tokuko Ushioda, Mari Katayama, Maiko Haruki, Mayumi Hosokura, and Your Perspectives, Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo |

| 2020 | TOKYO PHOTOGRAPHY RESEARCH Exhibition, Roppongi Tsutaya BOOK GALLERY, Tokyo The Body Electric, National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra ENCOUNTERS, ANB Tokyo, Tokyo |

| 2018 | Things So Faint But Real: Contemporary Japanese Photography vol. 15, The Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo Tsuka: An Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Photography, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne Corpus Lux, The Triennial of Photography Hamburg, Westwerk, Hamburg |

| 2017 | Calling/ re-calling, Kyoto University of Art and Design, Kyoto Homage to the Human Body, Galleri Grundstof, Aarhus RAP MUSEUM, Ichihara lakeside museum, Chiba |

| 2016 | Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival, Xiamen MACK chez colette, colette, Paris Shikijo: Eroticism in Japanese Photography, Blindspot Gallery, HongKong Close to the Edge: New Photography from Japan, Miyako Yoshinage, New York MACK CONCEPT TOKYO, IMA gallery, Tokyo |

| 2015 | Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival, Xiamen Horticulture Expo Garden, Xiamen Tokyo International Photography Festival, Art Factory Jonanjima, Tokyo |

| 2014 | Reflected – Works from the Foam Collection, Foam Amsterdam, Amsterdam G/P Collection Ⅱ, G/P+g3/ gallery, Tokyo |

| 2013 | Space Cadet Actual Exhibition #2, Turner Gallery, Tokyo |

| 2012 | Space Cadet Actual Exhibition #1, Turner Gallery, Tokyo oodee presents POV FEMALE TOKYO, CALM & PUNK GALLERY, Tokyo Natures, Gallery LWS, Paris |

| 2011 | untitled / image, Cultivate, Tokyo THE PHOTO / BOOKS HUB TOKYO, Omotesando Hills, Tokyo Mizu no Oto – Sound of Water, FOTOGRAFIA, Festival Internazionale di Roma, Rome Talent 2011, Foam Amsterdam, Amsterdam |

| 2010 | Yokohama Photo Festival, Yokohama Akarenga Soko, Yokohama NEW / ANOTHER FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY, Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, Tokyo The EXPOSED #5, CASO, Osaka |

| 2009 | Tokyo portfolio review, Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, Tokyo The EXPOSED #4, CASO, Osaka The EXPOSED #3.5, ART ZONE, Kyoto |

| 2007 | The EXPOSED #2, CASO, Osaka/Punctum,Tokyo Secret phantom, magic room?, Tokyo |

| 2005 | RECRUIT Hitotsubo award #25, Guardian Garden, Tokyo |

| 2004 | RECRUIT Hitotsubo award #23, Guardian Garden, Tokyo |

Publication

| 2022 | WALKING, DIVING, artbeat publishers supported by FUJIFILM Business Innovation Corp |

|---|---|

| 2021 | Fashion Eye Kyoto, Louis Vuitton |

| 2020 | New Skin, MACK |

| 2017 | Kawasaki Photographs, Cyzo |

| 2017 | Jubilee, artbeat publishers |

| 2016 | Transparency is the new mystery, MACK |

| 2014 | floaters, waterfall |

| 2014 | Crystal Love Starlight, TYCOON BOOKS |

| 2012 | Transparency is the new mystery, self-published |

| 2012 | Unknown Signals, oodee |

| 2012 | KAZAN, artbeat publishers |

Collection

Others

| Art Fairs | |

|---|---|

| 2022 | Art Collaboration Kyoto, Kyoto International Conference Center Event Hall, Kyoto |

| 2012-17 | UNSEEN PHOTO FAIR AMSTERDAM, Amsterdam |

| 2013-14 | Paris Photo, Paris |

-

Touchsight, Licklight

Hajime Nariai (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) 成相肇(東京国立近代美術館)

1.

I know what is photographed there. I know what it is called, too. I recognize the dark blue of cyanotype, the rippling crepe of the cotton fabric, and the little bits of silver thread embroidered near the edges. I recognize them, but I cannot tell you how these shapes and the blue and the wrinkles feel to me, the varied impressions they recall, the consciousness they awaken. Nor can I ever know what this string of words brings to your mind, the sensation that begins to stir inside of you. Even if you were here now, in front of me, and we could speak face to face.

Why are there always two parallel descriptions of the universe—the first-person account (“I see red”) and the third-person account (“He says that he sees red when certain pathways in his brain encounter a wavelength of six hundred nanometers”)? How can these two accounts be so utterly different yet complementary?

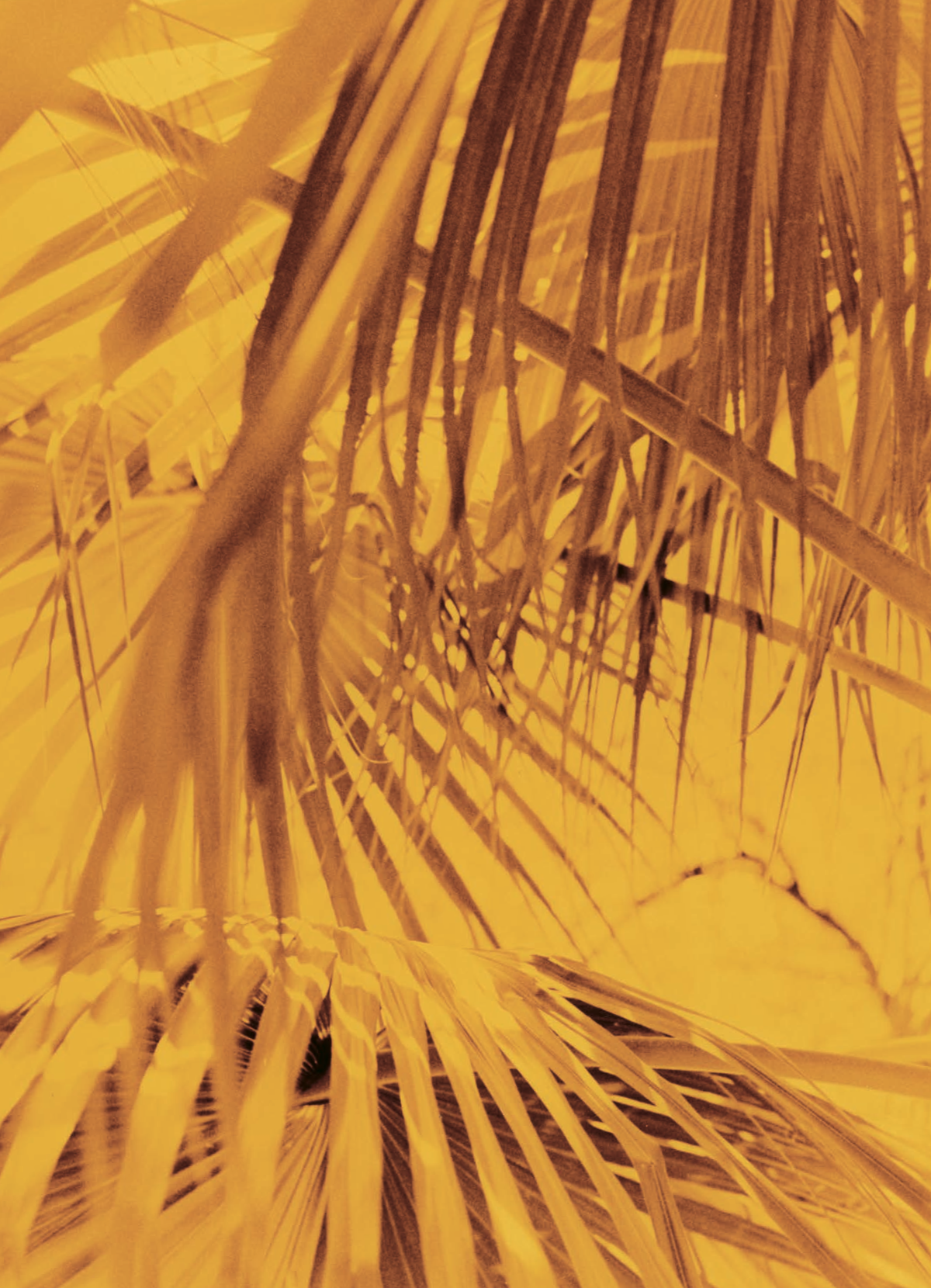

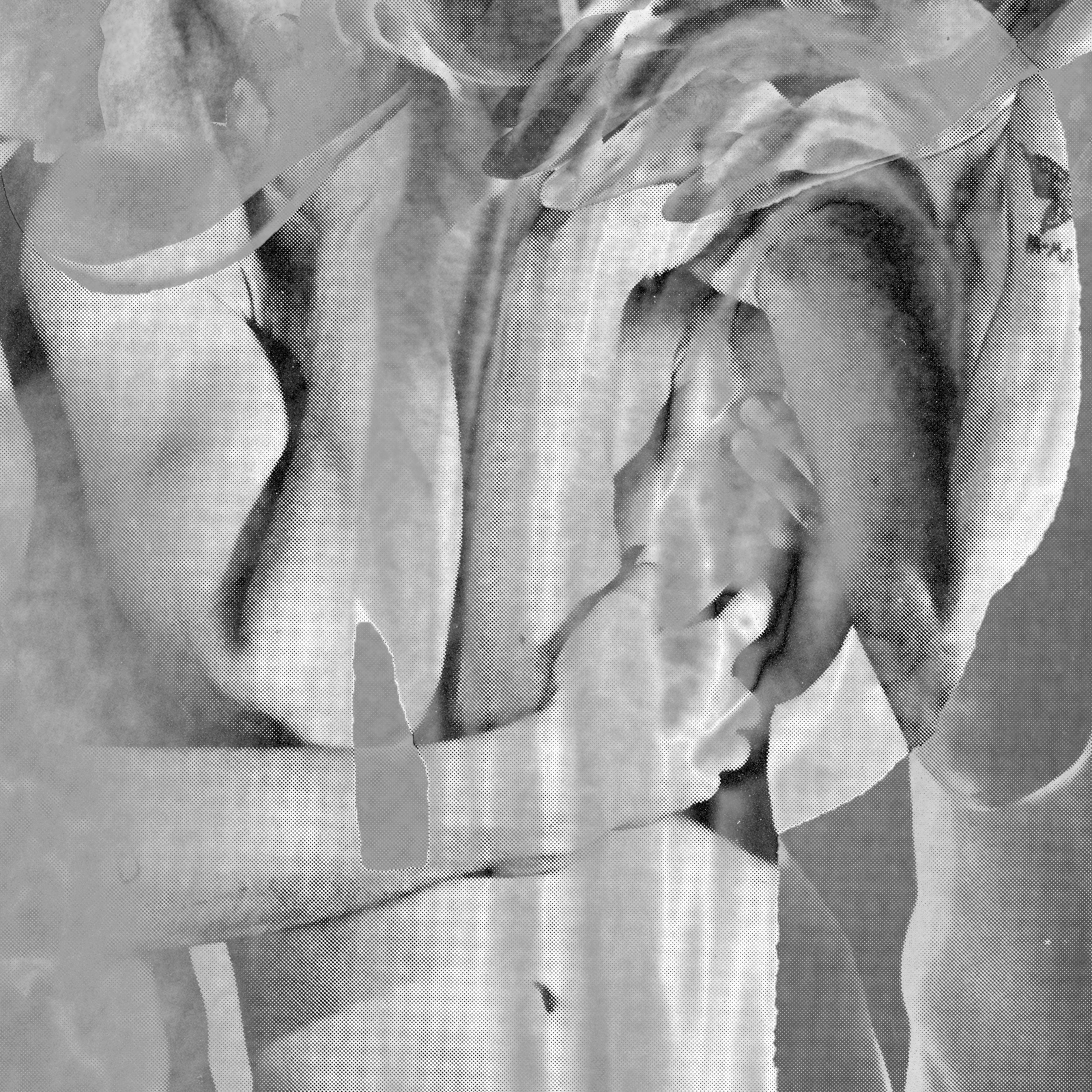

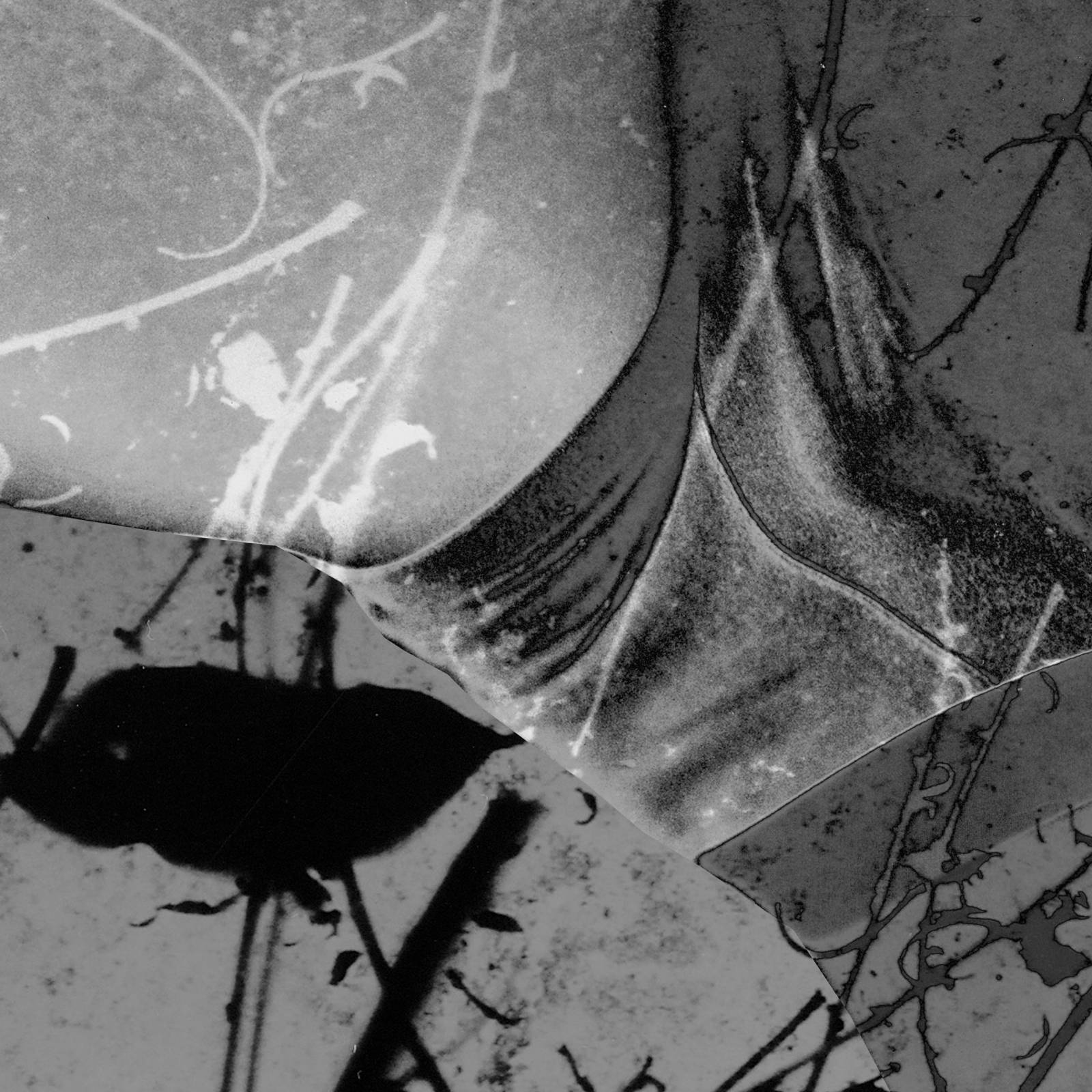

Since the beginning, Mayumi Hosokura’s photographic practice has been driven by an unwavering interest in (sharing) the experience that precedes the photograph itself. Her question is, in other words, one of qualia. Hosokura envisions “an experience more photographic than the act of looking at an actual photograph,” and “photographs that share a more personal vision, rather than function to demonstrate that objective sight = correct sight.” She asks: “To layer your own gaze over someone else’s, and as a result, be looking at something entirely different—what lies beyond this experience of sharing the impossibility of understanding?” By challenging the stillness of the still image, Hosokura invites in the uncertainty of vision.

We cannot communicate qualia—our lived perceptual experience of the subjective world—with others in the way that we experience it. The brain and the mind, the objectively observable non-self and the subjective self, are somehow separate. We still do not understand how physical matter in the brain can produce sensitivity, sensation, and consciousness, nor do we know how to confirm from the outside whether consciousness resides within a given system. Red is not visible in the data describing a wavelength of six hundred nanometers. We understand scientifically (that is, in the third person) how electric catfish sense electric fields through their skin, but it is impossible for us to know what it is like to feel electricity ourselves. Perhaps even the word “we” fails to stand collectively for the first person.

Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran’s answer to this question of qualia, long debated by philosophers, is that it is a matter of translation. The problem arises in the impossibility of translating between two languages that cannot understand each other—conventional written and spoken language and the language of nerve impulses. According to Ramachandran, if, instead of converting sensations into words, two brains could somehow be connected directly by nerve fibers, I could, in principle, experience the redness of your red, the pain of your pain, and even the qualia of electric catfish.Fig.1 Willem Kalf, Still Life with Drinking-Horn, c. 1653, National Gallery, London

Fig.2 Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine, c. 1658-1660, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

2.

In the 17th century, Dutch painters were wholly consumed by the desire to depict light as it reflected and transmitted across smooth surfaces such as ceramics, glass, and metal (fig.1). The process of carefully observing reflections and the images that appear within lit surfaces and depicting highlights through the application of paint required the painter’s eye to become a lens, or glass sphere, capable of collecting accurate information. In order to create a tromp l’oeil, the painter must first deceive their own eyes. Unlike the way that we perceive visual information in everyday life, discarding some elements in favor of others so as to process the world in an efficient and convenient manner, the painter must cast a net across their entire visual field, as though making a scan, with equal attention to all. They must fool the brain, which recognizes outline and intrinsic color, in the pursuit of a complete survey. The eye must be unfeeling. Yet to gaze at the world not as representation but as rays of universal light, to trace the ephemeral beams that shimmer not on the level of physical matter but on a higher plane—that is, to lick the light—is also associated with the experience of an invisible spirituality that cannot be perceived in a worldly sense (fig.2). As is well known, it was the camera obscura that enabled the eye to function for this purpose.

The inaccuracy of the human eye in comparison to the unfeeling camera eye suggests the existence of something on a subconscious level involved in (involuntary) perceptual processing. When painters peered through the viewfinder, they were seeking “phantoms in the brain” (Ramachandran), a precursor of human perception. What if we consider this relationship between the artist and the viewfinder-as-peephole in the present media environment? Nowadays, the viewfinder is not something to look through but rather installed by default into the world that is to be looked at. It turns on as soon we start up our devices, its presence marked only by an application name displayed in a corner of our screens; no longer do we pay it any mind. Who is the “finder” now?

Any space displayed through the viewfinder of an electronic device is, of course, artificial. But as neuroscientists have demonstrated through research on agnosia (the inability to recognize objects using one or more senses), and as Renaissance painters have long known, the system of human cognition has always been artificial. There is no point in chasing after the sentimental illusion of an authentic experience. So, if the computer is a simulation of the human brain, can it tell us how the electric catfish feels—tell us its quale—as it swims across the finder? Could something be shared through the translation of the nerve impulses for “photographic experience” or “individual vision”? Or if translation is too much to hope for, could at least the impossibility of sharing our respective qualia be conveyed, in reverse, through the still image? This is what Hosokura’s work offers us. There it is—something “other,” but connected to us in just the right way! Our very own electric catfish—the fingertip.3.

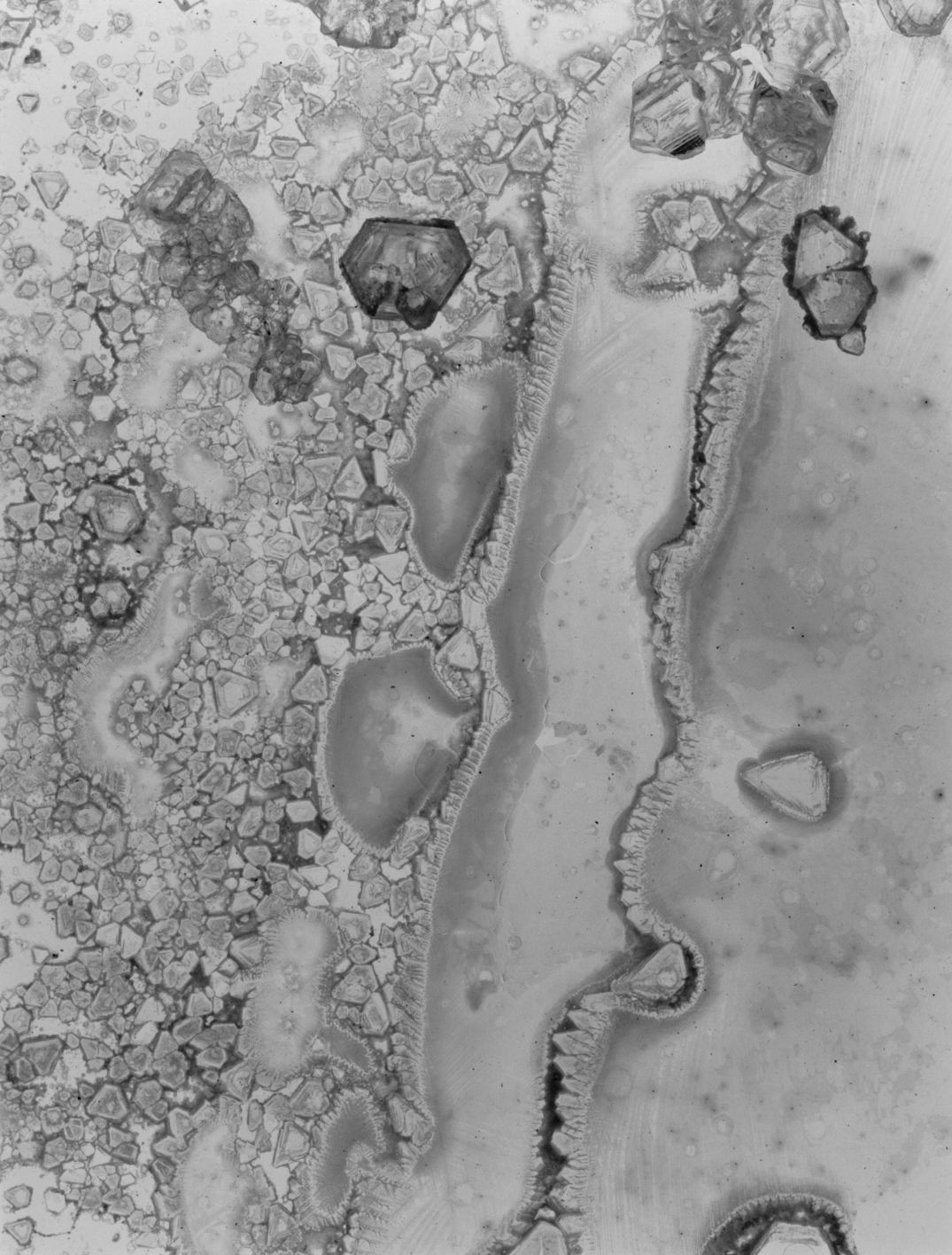

In recent years, Hosokura’s installations have been characterized by the central placement of display monitors, as if to serve as a control system for the photographs on the surrounding walls. In the exhibition walking, diving too, there are two vertically oriented monitors positioned back-to-back. One side displays a massive image Hosokura refers to as a “map,” comprised of photographs collected daily, then compiled and synthesized. The image on the monitor moves from top to bottom and left to right, magnifying and shrinking, as though manipulated by a touch screen. The cyanotypes hanging on the walls are snapshots of pieces of this “map.” On the screen, human skin makes an eerily seamless transition into the surface of an object. The movement of the image is disconcertingly independent of my own intentions (the motion feels less like a shifting of perspective and more like coerced touching). The occasional appearances of the black darkness that lies beyond the edges of the “map” are jarring. What is this video doing? Through her work, Hosokura attempts to convey the experience of something before it becomes “fixed,” but it would be an oversimplification to describe this video as a mere demonstration of the process of fixing an image.

The unbearable slowness of the scrolling motion—we translate this movement corporeally when we describe it as “heavy”—shows clearly that Hosokura’s display installations have always dealt with artificial haptic perception. In her exploration of it here, it is the monitor on the other side, which displays footage of a hand, that is especially striking. The screen presents a frontal portrait of the right hand as it moves within constraints, gesturing to swipe, pinch in, and stretch out. The strange, sluggish movement of the fingertips as they writhe in search of light—clearly an act of seeking, stroking, fumbling, and licking the light—is haunting. This video is not an explanation of Hosokura’s process of deciding which photographs to exhibit but rather indisputable documentation of the viewfinders and the eyes in the present moment.

The idea that fingertips can see and thus give rise to a new kind of qualia is entirely plausible. Dermatology researcher Mitsuhiro Denda goes as far as to describe skin as “the cerebrum expanded along the surface of the body.” The organ of skin, equipped with its own immune system, is at the frontline of the distinction between self and non-self. Skin is a sensor that receives stimuli and transmits information to the nervous system, and it is the interface between the environment and the living body.

I think I understand why Hosokura went so far in emphasizing tactility in this exhibition, working with cyanotype, a process that reveals the materiality of developing photographs, creating wrinkles in the cotton fabric, arranging the images as though a puzzle, and even embroidering them. This exhibition composes the world as seen through the skin on my fingertips, the world of another brain, indistinguishable from my own and yet a stranger to me. To treat the finger and the eye as equal subjects, as though to highlight the prominence of the iris and the fingerprint in biometric authentication, feels decidedly contemporary.4.

The eyeball is the sole surface of the human body that must not be touched by the finger.

Translation by Eriko Ikeda Kay

[1] Ramachandran, V.S. and Sandra Blakeslee, Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind, Quill, 1999, p.229.

[2] Hosokura Mayumi, “The Two Sides of the Eyelid Vol. 01 Photographic Experience,” Web Hanatsubaki, 2022.08.22, https://hanatsubaki.shiseido.com/jp/eyelids/19281/

[3] Hosokura Mayumi, Sen to Me exhibition text, 2021.9, https://tsca.jp/ja/exhibition/the-eye-draws/

[4] Denda Mitsuhiro, The Thinking Skin, Iwanami Shoten, 2005.

< Back to Text Index