Takuro Someya Contemporary Art is pleased to present part two of an exhibition of works by Nobuo Yamanaka opening on Saturday, July 15th.

Yamanaka was poised for an international breakthrough, having already participated in the Sao Paulo Biennale and the Paris Biennale, when he passed away suddenly at the age of 34, leaving behind roughly 600 hand-printed pinhole photographs created during his brief career of 12 years. Though these works lacked complete documentation and signatures by the artist, the Nobuo Yamanaka Estate Management Committee, established by the artist Kosai Hori, the then-chief curator of the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts Hirohiko Takeyama, and Yamanaka’s family under the leadership of the art critic Yoshiaki Tōno, with whom Yamanaka had been close, worked to identify and preserve them. Following a rigorous verification process, the photographs determined to be “works” were stamped with the committee’s seal, which was later destroyed, and their negatives were archived in the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts.

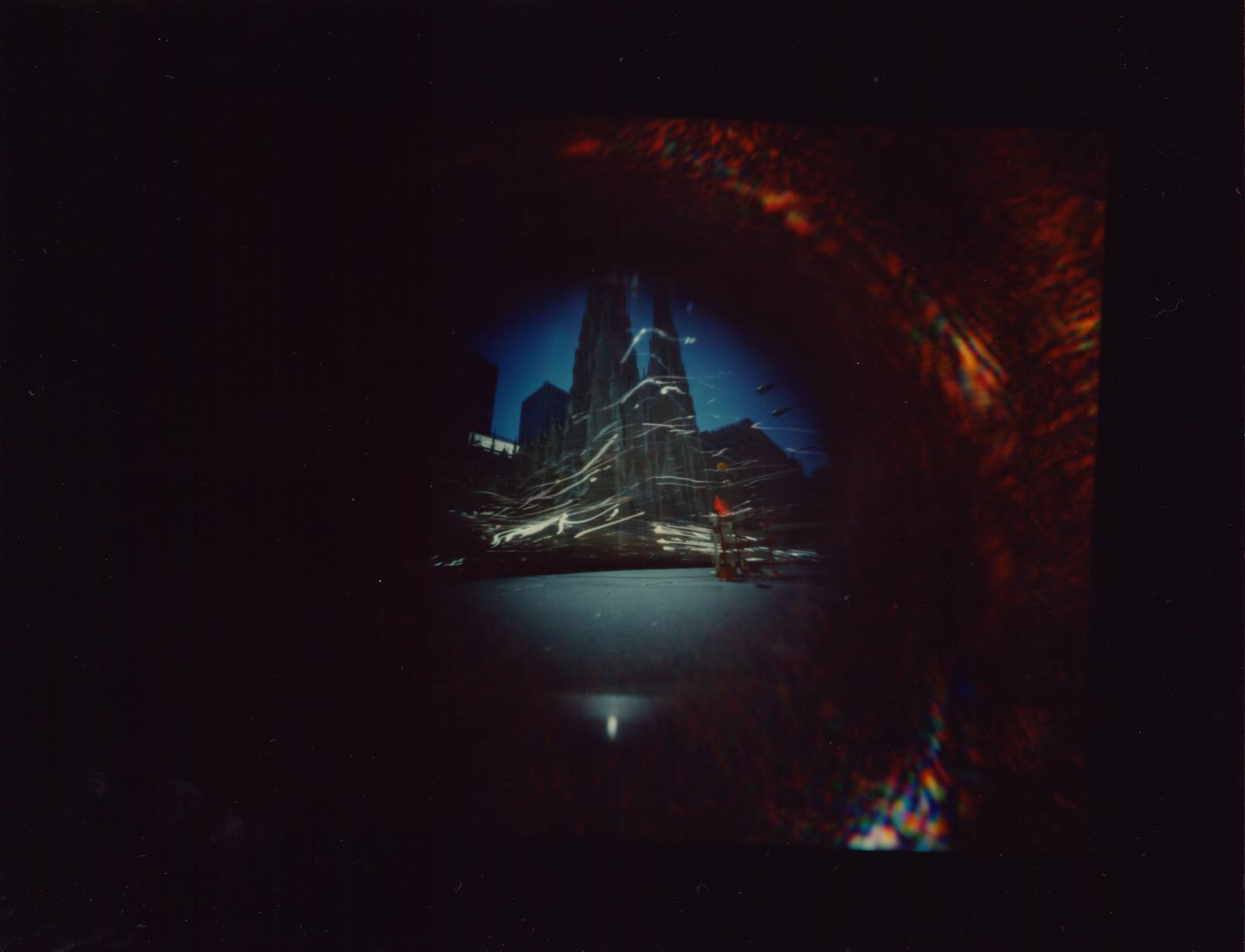

In part two of this exhibition, TSCA presents 16 works that bear the committee’s seal of verification from Manhattan in Pinhole, a series of pinhole photographs by Yamanaka in 1980, two years before he died in New York, alongside 16 previously unexhibited prints produced in the process of creating the series.

On Nobuo Yamanaka (Part 2/2)

Kenjin Miwa, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Part 1 pointed out the development and turn in Yamanaka’s work in 1973, after describing his debut work Projecting the Film of River on the River (1971) and Pinhole Camera (1972), where the viewer enters a camera obscura to look at the reduced and inverted image of the external world projected through a small hole. This turn, in short, involved the fixing of the image onto photographic paper, that is to say his works turned into photographs. What resulted was a severance of the image from the subject/subjective view inside the box, or a duplication of the subject/subjective view that allowed a part to go outside the box. (Read Part 1 here: https://tsca.jp/exhibition/nobuo-yamanaka/).

-4-

So, rather than photography, it was more about the temporal.

Even in my first work, River on the River, what I was doing by using film was thinking about time within the world. With the pinhole rooms, the exposure time grew longer and could extend infinitely, but at some point, you have to cut it. The same goes for the frame. It can grow infinitely, but you have to make a cut somewhere. But when I say cut, it’s not about cutting from the outside—it’s cutting from the inside. [emphasis mine][1]

The long exposure with pinhole cameras and the fixing onto photographic paper entailed, for Yamanaka, a foregrounding of the denotation of the work in terms of the severance of time and space (the fact that Projecting the Film of River on the River (1971) and Pinhole Camera (1972) are connected in terms of moving images means that the denotation of the works, that is, Yamanaka’s awareness of time and space in relation to the conditions of the works, bridges the two). As explored at the end of Part 1, the detachment and duplication/exiting from the box of the subject is one method to achieve this severance of time and space. The camera obscura has been interpreted as a model of vision in which the subject inside the box receives the world outside of the box through a hole bored into the wall (as an image that is cut out by the hole). While adopting this method, the severance of time and space as conceived by Yamanaka does not happen at the locus of the subject “inside” the camera obscura. Neither is it achieved in terms of standing “outside” to have an overview of (in other words, to objectify) the structure composed of subject-wall/hole-world. Yamanaka’s expression “cutting from the inside” does not pertain to the boundaries of a box or a frame, but rather to cutting from inside the world. Yamanaka got out of the box in order to cut out the world from inside the world, that is to losing connection with the world through the severance.

-5-

You know, I was in the alpine club in high school. And when I’d go to the mountains and look at the landscape, I had this kind of feeling of dissolving into it.[2]

It’s not really about spatiality since I am in that space too.[3]

The sense of cutting from the inside by getting out of the box, or cutting out the world from within the world, is palpable in the three-part series Machu Picchu in Pinhole, Manhattan in Pinhole, Tokyo in Pinhole that was produced in 1980 and 1981 (photographed using 4×5 or 8×10 film and contact printed onto photographic paper). Yamanaka commented as follows about one of the images in Tokyo in Pinhole: “Do you see how there is something blurry near the center of the fence? That’s actually me. I went and sat there from time to time during the exposure. The surroundings and I had different exposure times so I appear translucent in the image.”[4] The viewer sees Yamanaka’s presence imprinted into the photograph like a ghost. The relationship between the world and Yamanaka here is not something linear, binary, and static like subject-wall/hole-world. Yamanaka moves within the world.

The time that Yamanaka turned the space of the gallery into a pinhole camera in May and June of 1977 at the Galerie Liliane et Michel Durand-Dessert near the Pompidou Centre in Paris (inaugurated in April of the same year) is a striking foreshadowing of his three-part series in the 80s: “I used to always look towards the gallery from the hill of Sacré-Cœur, and enjoyed looking out for the weather, thinking ‘today’s sunny so it should look clear,’ or ‘today’s cloudy so it’s probably not showing up well.’”[5] It would have been impossible to see the “figure” of Yamanaka standing on the distant hill from inside the gallery. A mirage-like image emerges, however, of one person’s gaze existing both here and there, at the same time. (The fact that, two years earlier, Gordon Matta-Clark had produced Conical Intersect (1975), a work where a conical hole implying the cone of vision penetrated a building near the then-under-construction Pompidou Centre, is an interesting harbinger. Matta-Clark also held a solo exhibition at Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris around the same time as Yamanaka’s exhibition. Did they, perhaps, see each other’s exhibitions?)

In the 1973 pinhole photograph series, the impression is more of opening a hole from the inside, or of going from here to over there. It is like stepping timidly out of the box (darkness). In contrast, in the series in the 1980s, there is a strong impression of that “over there” coming toward here, due to images of translucency, images of the sun itself, and particularly the brilliant rings of light that frame the holes (which apparently form because of the thickness and unevenness of the pinholes). What is this something that comes toward? “Dissolved” into the translucent images, in the sun, and in the rings of light, is Yamanaka himself, his gaze cast this way from inside the world.

-6-

I did River on the River in Tama River in 1971. A screen is a limited space, but in that case, “space” was not about a limited space, but the world. You see very well outside of the space where the film is projected.[6]

In the modern era, a work of art was regarded as something that should be cut out from the world (by the author), something that should be autonomous and complete within the frame. It is undeniable that the limitless world itself cannot be represented and that a work must in one way or another make a cut and close off. However, Yamanaka’s works were not primarily concerned with producing an object that is self-sufficient in terms of how time and space were cut out to produce an artwork. His photographs refuse objectification and fixing as a thing, and rather flow out of the enclosure like a river and diffuse like rays of light. They point precisely at the fact that there are countless objects and events beyond the effusion and diffusion that are governed by entirely different principles from those at play within the work. Yamanaka may never have fully realized such thinking and practice. Along this path lies a horizon which, for example, could connect with the concerns of Robert Smithson, who thought about the conditions of the world going beyond the question of “inside or outside of the museum” (as it is often misunderstood), while also being conscious that artworks are destined to be delimited in some way. In a text he wrote in 1971,[7] Yamanaka quotes the following passage from Smithson’s important text entitled “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey.”[8] (Yamanaka learned of this quote from a 1969 text by Teruo Fujieda,[9] and probably never got to know the entirety of Smithson’s text.)

Noon-day sunshine cinema-ized the site, turning the bridge and the river into an over-exposed picture. Photographing it with my Instamatic 400 was like photographing a photograph. The sun became a monstrous light-bulb that projected a detached series of “stills” through my Instamatic into my eye. When I walked on the bridge, it was as though I was walking on an enormous photograph that was made of wood and steel, and underneath the river existed as an enormous movie film that showed nothing but a continuous blank.

When peering into a circle measuring a mere 10 centimeters in Yamanaka’s photographs, the viewer is half-assimilated to the gaze directed at the landscape that is imagined to be that of Yamanaka, but at the same time also perceives Yamanaka looking toward the viewer while being dissolved in the landscape. The image that appears to show a commonplace view indeed makes visible an event that should not be visible, that has never been seen. This surprise destabilizes the solidity of the place that is here and now which we, the viewers of a photograph, never questioned. This is, of course, to be welcomed. Let us celebrate the richness, complexity, and the certitude of the “world” that Yamanaka’s photographs present.

Translation by Naoki Matsuyama

[1] Nobuo Yamanaka and Tetsuya Watanabe, “Eizō taidan—Eizō bijutsu sappō,”[Dialogue on video: Killing with video art], Bijutsushihyō, no. 9 (May 1978): 31-32.

[2] Ibid., 30.

[3] Ibid., 31.

[4] Nobuo Yamanaka, “Pinhōru shashin. Renzu no nai kamera de toru shashin (Intabyū)” [Pinhole photos. Photographs taken with cameras without a lens. (Interview)], Imēji no bōken 7: Shashin [Image adventure 7: Photography] (Kawade Shobo, 1982), 92.

[5] Nobuo Yamanaka, “Pari de sutesokonatta pinhōru” [The pinhole I almost threw away in Paris], Bijutsu techō, no. 426 (November 1977): 107.

[6] Yamanaka and Watanabe, ““Eizō taidan,” 30.

[7] Nobuo Yamanaka, “Bijutsukan o hanarete” [Leaving the museum], Bijutsushihyō 3 (October 1971).

[8] Robert Smithson, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey.” Originally published as “The Monuments of Passaic,” Artforum 6, no.4 (December, 1967): 49.

[9] Teruo Fujieda, “Kan’nen no romanthishizumu: Busshitsu no shōmetsu” [The romanticism of the concept: The disappearance of matter], Bijutsu techō, no. 315 (July 1969): 104-105.

Part One: Saturday, May 27, 2023 – Saturday, July 1, 2023

Part Two: Saturday, July 15, 2023 – Saturday, August 19, 2023

Summer Holiday: Wednesday, August 9 – Wednesday, August 16

Open: Tues – Sat 11:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.

Closed: Sun, Mon, and National Holidays

TSCA 3F TERRADA Art Complex I 1-33-10 Higashi-Shinagawa

Shinagawa-ku Tokyo 140-0002

tel 03-6712-9887 |fax 03-4578-0318 |e-mail gallery@tsca.jp