Masaru Iwai

Exhibition at TSCA

- Masaru Iwai | Control Diaries 5 September - 10 October, 2020

- Masaru Iwai | Perspective of Familiarity 9 September - 14 October, 2017

- Masaru Iwai | Passed Places, Passed Things 21 February - 20 March, 2015

- Masaru Iwai | Dancing Cleansing 12 November - 10 December, 2011

- Masaru Iwai, Mitsunori Sakano | Spontaneous Order 30 April - 5 June, 2010

Profile |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Awards |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Solo Exhibitions |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Group Exhibition |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Publication |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Collection |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Others |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Profile

| 2009 | Received Ph.D. in Fine Arts at Tokyo University of the Arts |

|---|---|

| 1975 | Born in Kyoto, Japan |

Awards

Solo Exhibitions

| 2021-22 | HOW TO CLEANUP THE MUSEUM, Fuchu Art Museum, Tokyo |

|---|---|

| 2020 | Control Diaries, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo Identity XVI - My Home? – curated by Kenichi Kondo, nichido contemporary art, Tokyo |

| 2018-2019 | Kireinisuru, H∞L Gallery Hachinohe Gakuin Junior College, Aomori, Japan |

| 2018 | Ahuredasu, gallery circlo, Saga, Japan |

| 2017 | Perspective of Familiarity, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo Tokedasu (Starting to Melt), Saga Saiko Festival 2017, gallery circlo, Saga, Japan |

| 2016 | A Prisoner of HabitーStaring, Reproduction, Sucking the Thumb, Akita University of Art, BIYONG POINT Gallery, Akita, Japan Mawaridasu (Beginning to Turn), Saga Saiko Festival 2016, gallery circlo, Saga, Japan |

| 2015 | A Prisoner of HabitーDance, Eat, Defecate, Akita University of Art, BIYONG POINT Gallery, Akita, Japan Passed Places, Passed Things, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo |

| 2012 | What happened on the pool ?, Asagaya, Tokyo |

| 2011 | Mutation at the dead end, 3331 Gallery, Tokyo Slow, Down., Art Center Ongoing, Tokyo Dancing Cleansing, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo |

| 2010 | Park Cleansing, Château Koganei, Tokyo The M.I.X. ‒ All clean/ever dirty, Treasure hill artist village, Taipei |

| 2009 | Clean up 1.2.3., Art Center Ongoing, Tokyo Polishing Housing, monné porte, Nagasaki, Japan |

| 2008 | Cleaner’s high #1, Otto Mainzheim Gallery, Tokyo |

Group Exhibition

| 2022 | Seeing as though touching Contemporary Japanese Photography vol.19, Top Museum, Tokyo |

|---|---|

| 2020 | Yokohama Triennale 2020 AFTER GLOW, Yokohama Museum of Art, Kanagawa, Japan My Home?, Nichido Contemporary Art, Tokyo |

| 2019 | Artisterium, David Kakabadze Fine Art Gallery, Kutaisi, Georgia |

| 2018 | Unfixed Perspectives, Yokohama Civic Art Gallery, Yokohama City, Japan |

| 2017 | REBORN ART FESTIVAL 2017, Miyagi |

| 2014 | Asia Anarchy Alliance, Tokyo Wonder Site, Tokyo 3331 Art Fair, 3331 Arts Chiyoda, Tokyo Backyard stories 2014, Batumi, Georgia |

| 2013 | Am I you?, G. Leonidze Museum of Georgian Literature, Georgia Now Japan, Kunsthal KAdE Amersfoort, Netherlands NEEDLESS CLEANUP, Meet Factory, Prague Maintenance Required, The Kitchen, New York ROPPONGI ART NIGHT 2013, 7-7-16 Roppongi, Tokyo |

| 2012 | Tokyo Story 2011, Tokyo Wonder Site, Tokyo White Night, A.I.R. Cambodia, Phnom Penh |

| 2011 | Artisterium 2011 -Free fall-, Tbilisi, Georgia Drop me! C.P.U.E.2011, nitehi works, Yokohama, Japan TERATOTERA Festival -POST-, Tokyo On the agenda of the Arts -Where do we go from here?-, Tokyo Wonder Site Shibuya, Tokyo Home, Sweet Home, Tama Art University, Tokyo Tokyo Story 2010, Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, Tokyo |

| 2010 | Spontaneous Order, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art, Tokyo How to invert urbanism, Asahi Art Square, Tokyo Koza Crossing 2010, Koza-Gintengai, Okinawa, Japan |

| 2009 | Re: Membering. Next of Japan, LOOP / Doosan Gallery, Seoul, Korea Memory / State, Museum of Jiangxi Normal University, China Dream of Midsummer, Chinzan-so, Tokyo Hiroshima Art Project [KIPPOUMARU], Hiroshima, Japan Koza Crossing 2009, Koza-Gintengai, Okinawa, Japan |

| 2008 | A multi-faced mirror, Japan Homes model house space, Tokyo Doctoral Final Exhibition, The University Art Museum, Tokyo Wanakio 2008, Naha, Okinawa, Japan |

| 2007 | Double Cast, Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, Tokyo |

| 2006 | SWITCH, Keio University, Kanagawa, Japan |

| 2005 | The Road not Taken '05, Gallery Sowaka, Kyoto, Japan Voice of Site, Visual Arts Gallery, New York Sustainable Art Project 2005, Tokyo |

| 2004 | Graduation Works Show, Tokyo S.I.C.E 2004, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Voice of Site, Tokyo Sustainable Art Project 2004, Tokyo |

| 2003 | Outcomes of one time and space, Moyland, Germany S.I.C.E 2003, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Junction, Tokyo |

Publication

Collection

Others

| Art Fair | |

|---|---|

| 2020 | Yokohama Triennale 2020 |

| 2012 | Art Fair Tokyo 2012, Tokyo International Forum, Tokyo |

| Collaborative Projects | |

| 2018 | Ghosting (Performative Dance Piece), CHART Art Fair, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| 2016 | x / groove space (Performative Dance Piece), Japan, Germany |

-

What Emerges Beyond Repetition and Noise

Toshiaki Ishikura 石倉敏明

Washing, eating, cleaning and excretion are motifs that make repeated appearances in Masaru Iwai’s work. What, indeed, is the common context that connects this series of acts? On the surface, the space that we regard as “society” appears to be sustained without incident by means of face-to-face communication between individuals, the transmission of information through letters and symbols, and the exchange of money for goods. Behind this system of order, however, exists the repetition of actions carried out by each member of society to sustain their respective lives, which seemingly blend into the everyday landscape as a matter of course. The repetition of such actions, which we always witness yet have a tendency not to perceive, are not only implemented within social groups, but are also similarly repeated at the scale of an individual’s body.

There are habitual acts that we repeatedly engage in every day without question. Iwai spends time living in various parts of the world where he observes the repetition of these quotidian acts and brings to light the reality that lives within them. For example, the act of washing is incorporated into the series of processes that we engage in as a means of managing our biological bodies in a context that is separated from the social/symbolic body. We, as human beings who possess social/symbolic bodies, are indeed at the behest of a society that requests us to rid ourselves of any bodily waste that is produced from within us, such as grime, sweat and excrement, as well as various kinds of other dirt and odors, to maintain a state of hygienic cleanliness. One could say that the demand for home appliances, from washing machines to flushing toilets, modular bathrooms and fitted kitchen systems, is testimony to this fact. What if, however, things such as food, living creatures or excrement had accidentally found their way into a washing machine constructed and societally designated for washing clothes? What kind of meaning does the act of washing have within the framework of society in the first place?

For those leading a contemporary urban lifestyle in which the act of washing clothes has been optimized through the functions of detergent and washing machines, it is perhaps difficult to imagine the lives of people who use cold water from rivers and drainage spouts for washing. The waterside is a common resource that is used by both humans and other creatures, and is indeed not a space that has been created solely for the purpose of washing clothes. For example, in some parts of South Asia where the river is not only a place to catch fish for eating but also used for washing dishes and clothes, bathing, and even in some cases scattering the cremated ashes of the dead, the practices of washing clothes differ from those of city-dwellers equipped with washing machines and drainage facilities.

Historically, the establishment of water delivery systems and progress in flood control see the use of water in society become specified according to lifestyle tasks such as cooking and washing. Water comes to be managed based on purpose, such as wells for drinking water, designated places for washing clothes, designated places for bathing, water tanks, fountains and toilets. Archaeologists have noted such changes in social awareness in societies around the world. For example, Yvonne Verdier documents various provisions introduced in France in the late 19th century to avoid confusion regarding water-related tasks. In 1883 in the village of Minot near Dijon, the following regulations were issued regarding the use of fountains:

Rule 1: It is strictly forbidden to wash clothes, horse tools, potatoes, vegetables, bottles, pans and other unclean things in the reservoir of a fountain that is designated as a water drinking facility.

Rule 2: Likewise, it is strictly prohibited to wash vegetables, potatoes, horse tools, pots, animal entrails and other unclean things in a reservoir or vicinity of an area that is designated as a washing facility. The only things that can be washed are sheets, cloths, and other general items of clothing.[1]

Such studies by archaeologists illustrate a change that occurs in the awareness of residents when a certain community designates environments for water usage according to purpose. For example, when a water facility specified for washing is created within a town, the awareness of people who until then had engaged in all kinds of water-related tasks in one place inevitably begins to alter. In these instances, the mixing of other water-related tasks, such as the washing of dishes, meat or vegetables, bathing and hair washing, or the keeping of ornamental fish in a place designated for washing clothes would indeed be considered acts disrupting social order and local hygienic codes, and thus prohibited. In comparing circumstances before and after such a ban, there is no doubt that the lifestyles and physical habits of residents would also change.

The purposes and hygienic standards of places of water are in the same way inherited into the contemporary living context, where the setting for washing has shifted to functional micro-water environments such as residential water facilities and kitchens, bathrooms, toilets, water tanks, washbasins and washing machines. What is in part automatically washed away and drained in these places is the “chaos” that is removed from the “cosmos” of society, and in terms of the world of acoustics, equates to what is referred to as “noise.”

In one of his representative works, Galaxy Wash (2008), Masaru Iwai attempts to bring to light that which is conceived while simultaneously torn between such cosmos and chaos, or rhythm and noise. Various things emerge (i.e. are washed) one after another within a murky tank of detergent and water. The objects washed in this video work are not only dishes, but also objects that belong to completely different categories, such as meat and vegetables, a stuffed toy, books, shoes and a pair of sunglasses. By mixing together things with distinct classifications from one another in social space to realize impossible circumstances, Iwai succeeds in disrupting social common sense regarding washing implemented on a local level, thereby highlighting the dimensions that we unquestionably consider to be a matter of course. That being said, this is not all there is to Iwai’s endeavor. This work, as a video document of the act of washing, is not a simple pursuit of aestheticism in terms of optics and color: rather, it also reflects a sense of power in generating order harbored within the detergent as a medium and in the symbolic procedure of washing.

What is present within the translucent water in which the detergent has dissolved is a pair of hands that continue to engage in the act of washing, with objects like a piece of meat and a book that has already been cleaned drifting close by. In the same water, one can see fish swimming while eating fragments of food that has crumbled away. The video footage, in which things of different genres, from food to tools, accessories and fish, come together in the soapy mix of detergent and water, may indeed disturb the viewer’s senses and cause discomfort. What waits beyond this disturbance, however, is another sense of aesthetic that receives and even accepts the dirt and impurities that are removed, discarded and forgotten through the process of washing. One could perhaps describe this as the aesthetic of noise that erupts from the rifts in social space. Galaxy Wash reminds us of the fact that the act of washing itself serves to create a sense of order (i.e. “cosmos”) that is in a motional state, in an image very much like the galaxies that float in the night sky.

What is expressed here is not only a situation in which the system of order conceived through washing exists simultaneously and in a multi-tiered manner with the dirt (i.e. noise) eliminated as a result, but also the relationship that exists between things in a place separated from human interference, very much like stars rotating and orbiting within a galaxy. The objects dynamically swirl within the tank, floating and sinking precariously and gradually turning the water murky, in the process destroying the sense of order that existed only a moment ago, enabling a microcosmic galaxy to emerge.

As the British anthropologist Mary Douglas articulated, order in the human world is ensured through means of a classified symbolic system. That which embodies a sense of ambiguity that transcends this classification, however, is regarded as a threat to society as an element that disrupts socially classified order. For example, saliva, excrement and blood are regarded as normal when circulating within the human body, yet the moment they leave the body and are placed in social space they give rise to intense feelings of disgust as forms of “dirt” and “noise.” Nails and hair are also considered acceptable as social scenery so long as they are a part of the body, but when they are separated from the body, they call for a pressing urgency to be discarded as “dirt.” Likewise, items of food served on beautiful plates will continue to remain clean objects so long as they are presented upon a clean table or dining area. If presented “out of place” somewhere amid accumulated piles of excrement and garbage, the food would no doubt instigate an intense feeling of filth and contamination. Sensations of dirt are caused by disruptions to symbolic order. It is within this very context that Douglas had discovered the roots of social taboos and manners.[2]

Cosmetology on the street is a work that documents a series of actions concerning the treatment of dog excrement, which one could indeed refer to as “noise” on the pavement. Dog excrement left on the pavement is not in itself something that is particularly uncommon within the cities of Europe. In this work, however, gel-like fluids such as antiperspirant and emulsion are squeezed out onto the excrement, applying “cosmetics” to it as if continuing to engage in a devastatingly vain struggle. Moreover, the excrement is abruptly burned, after which new cosmetics are again relentlessly squeezed out onto its cinders. The excrement becomes a negative of the human face due to the presence of fake eyelashes that have suddenly been applied to it, and through the use of the word cosmetology (i.e. cosmetic techniques) in the title, the viewer is made aware of the implication of beauty instilled within the work. Dog excrement, which exists as a foreign body in the street, a space maintained for human traffic and urban transport, gives rise to a sense of dizziness in those who view it by being adorned with cosmetics, which are considered traces of aesthetic order. The sense of contamination is thus clarified through this encounter between dog excrement and cosmetics on the street, and the scenery of a clean street is decisively de-humanized.

The excrement of dogs, which are essentially partners for human beings, in the context of urban life, conveys the ambiguous boundary between humanized nature and naturalized culture. The dog excrement that is encountered on street corners in Europe appears all the more out of place when the town presents a solid, stone-built atmosphere, and the more it resonates with a refined aesthetic. Nevertheless, Iwai punctures this sense of awkwardness, and as if to emphasize the heterogeneity of the city in the context of the organic matter of excrement, brings to the foreground the technique of cosmetology as that which is involved in the creation of the “cosmos” (i.e. order) from which the term itself is derived. Cosmetology is indeed a technique that brings order to the human face, and this cosmos is contrasted with the chaos that precedes it. By applying this technique to dog excrement, Iwai accentuates the rich textures of material-symbolic practice that occur within the backdrop of social life, where people live their everyday lives as a matter of course, and attempts to discover the dynamism of collective action that exists beyond the dichotomy of cosmos and chaos.

This confrontation is conveyed repeatedly in 100 Fishes / Before and After of Epicure (2014), a work that was produced in Georgia. It consists of scenes of fish (trout) that have been arranged on a table in preparation for dining, and scenes that capture the remains of the same fish after they have been eaten. What emerges within this work is the figure of an artist who is deeply involved in the society where his work is filmed, and never abstracts his physicality. Before being eaten, the fish are raw objects that exist in the moment just before crossing over the large boundary from living thing to food, and from nature to culture. However, after they have had their internal organs removed, and are then cooked and eaten, their bodies (i.e. flesh) indeed become part of the energy and bodies of the people who devour them, coming to circulate through their internal systems. The physical micro-cosmoses of such individuals and the macro-cosmos within which the fish originally lived do not exist separately: rather, they are inextricably connected through the techniques of transforming living things into edible food—in other words, through culinary skills.

Here, the uneaten bones, fish heads and removed innards are not simply discarded as garbage. At the end of the video, after the tablecloth has been tidied and the table put away, the cat that remains is indeed a presence that embodies the very circulation of waste and the system of ecology within the city. That is to say, what emerge are the residuals that cannot be wiped cleanly away through means of collective cleansing and acts of washing. These residuals of reality, at least for the cat under the table, are a legitimate source of food.

Iwai consciously attempts to form a connection between these residuals that cannot be wiped away and those that emerge in the acts of cleansing and dancing. The video work Dancing Cleansing—Bon Dance, Akita (2015), which was produced as a result of his residency in Akita Prefecture, presents people dancing in several styles of Bon dance alongside those who engage in acts of cleaning, washing and cleansing. After participating in the lifestyle and intensely studying the practices of Akita’s Araya region, Iwai worked with the local community and its students to revive styles of Bon dance and songs that had once fallen out of practice. In succeeding in doing so, perhaps what he awakened were not only the memories of the forgotten arts of the region, but also the forgotten bodies of the deceased—Bon dances are meant to welcome the spirits of one’s ancestors—and the aesthetics of repetition and noise that are reminiscent of Tatsumi Hijikata’s Butoh performances. When one considers the synchronicity of dance and acts of cleansing from this perspective, the collective others that repeatedly appear within his work—groups of innumerable “cleaners” who clean away the accumulated dust of time—appear to present themselves as an aggregated force that tries to distinguish between life and death, as well as separate this world from the afterlife through the traditional Japanese practice of sweeping the grounds with a bamboo broom after a funeral. Nevertheless, at times we attempt to reunite with the deceased within the same circle in a realm that transcends the boundaries of life and death, embracing the fleeting moment of engaging in a dance together.

< Back to Text Index

[1] Yvonne Verdier, Façons de dire, façons de faire. La laveuse, la couturière, la cuisinière (Paris: Gallimard, 1979).

[2] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, translated by Toshiaki Tsukamoto (Tokyo: Chikuma Gakugei Bunko, 1972).

-

Violent Hygiene and Contextual Dirt

Nina Horisaki-Christens

The screen is filled with a white cloth on which thirty or so real fish have been lined up, filling most of its lower left corner. Human hands and heads enter the screen from the edges, placing more fish on the cloth until the entire screen is filled with an immobile school of irregularly placed fish. Now hands with knives and scissors move in from the edges, slicing into the fish bodies to remove slimy, dark pink guts, sometimes forcefully, at other times with minimal effort. Gutted fish are placed near the corners and edges of the screen, innards collected in a few separate piles. Hands covered in bloody remains occasionally wipe the cloth, leaving streaks of red and light brown across its once-white surface. As the gutted fish are removed, traces of their presence are left behind in the form of liquids—water, guts, blood and oils—that stain the cloth. On-screen movement ceases for a few moments, the pause in action presenting us with a composition of hand streaks, traces of gutted fish, heaps of fish innards and a small pile of knives with one lone knife off to the side. The moment is further punctuated when the screen goes black, only to return to the same composition a moment later.

This protracted scene has a painterly quality that seems to sit aesthetically somewhere between Jackson Pollock’s Full Fathom Five, Kazuo Shiraga’s Wild Boar Hunting II, and a Hermann Nitsch Schüttebild painting. Somewhere between material expression and ritual, the violent action captured in this image conjures the ghosts of high modernism and its performative offshoots.

Yet as becomes clear when the onscreen action resumes a minute later, this is but one stage in an ongoing process. Eventually napkins and plates join the scene, then a used grill and a tray of drinks. Hands move in to clear away these remains, clear off the cloth, fold it up, and disassemble the table beneath. Throughout this visual development, the soundtrack is consistent: we hear the background noise of a party, with half-discernable voices occasionally rising above the overall murmur, but never crystallizing into full statements or conversations.

Unlike the dramatized mimicry of violence found in Pollock and Shiraga, or the shocking performative violence of Nitsch, Masaru Iwai’s 100 Fishes presents unstaged violence as anti-drama, embedded in the cyclical processes of cleaning, consuming and tidying up from a communal fish feast. In fact, across Iwai’s investigations of cleaning habits and rituals, boundaries of dirt and refuse, and the value systems that maintenance reveals, we find formalism and aesthetics rubbing up against conceptual and literal violence. It is this tension between the perceived virtue of cleanliness, especially as a marker of modernization and modernism, and the violence it effects within mundane spaces of the everyday, that lies at the heart of Iwai’s oeuvre.

One way in which this violence comes into focus in Iwai’s work is through destruction effected by cleaning processes taken to absurd extremes. In the video Polishing Housing (2009), it is the process of sanding the surface of a wood-and-drywall structure—an act meant to refine the surface—that, continued beyond reasonable limits, leads to the complete disintegration of the construction. The form is reduced to a window and door haphazardly perched within the remnants of studs, piles of wood and plaster dust.

This potential for destruction is a recurring aspect of Iwai’s works with cleaning detergent as well. As Iwai himself points out, detergent is effective at cleaning because it is, in essence, a poison inimical to organic life. Just as it kills bacteria, it holds the potential to injure or kill people if ingested in large amounts. Yet as we use it to clean tableware, cooking surfaces and even fruits and vegetables, we inevitably ingest small amounts of it on a daily basis. Thus, in the performance Washing Stage (2013), a series of objects including dishware, vegetables, fish, bread and meat are performatively “washed” with soap, sans water, atop a black, plinth-like stage. Soap coats the surfaces of these objects in a thick layer, dripping onto the stage below at the same time it is absorbed into the surfaces of the objects. The soap dripped on the stage, mixed with blood and oil from these objects, is left as a trace of the performance, destroying the once-pristine nature of the black plinth’s surface.

This mingling of “clean” soap with “dirty” blood and oil also points to another kind of destruction adopted by Iwai’s work: the destruction of category boundaries central to ideas of cleanliness and hygiene. As Mary Douglas points out in her classic study Purity and Danger:

[D]irt is essentially disorder. There is no such thing as absolute dirt: it exists in the eye of the beholder. If we shun dirt, it is not because of craven fear, still less dread of holy terror. Nor do our ideas about disease account for the range of our behaviour in cleaning or avoiding dirt. Dirt offends against order.[1]

Perhaps ironically, Galaxy Wash (2008) performs an attack on order through the medium of soap, in this case also mixed with water, that violates the boundaries between categorically different types of objects. Shot looking up from below a glass aquarium, a pair of hands proceeds to use a sponge to wash a series of objects submerged in the water. Starting from glass and ceramic cups, the hands quickly move on to foods such as carrots, tofu and meat, as well as other objects including a book, a sneaker and glasses. As each item is washed and dropped to the bottom of the tank, accumulating between the video camera and the disembodied hands, particles falling off the objects render the water increasingly murkier. Our vision is literally impeded at the same time the classificatory schemas we use to distinguish different types of items are violated. Viewers may at first cringe as a sneaker is washed next to a steak, but why? Is there a reason to treat them differently when submerged in soapy water? Is this discomfort due to an actual concern regarding bacteria, or a more ambiguous but perhaps irrational fear of contamination born of the violation of categorical distinctions?

Of course these schemas extend beyond the question of what is being cleaned to how cleaning takes place: the formal qualities of cleaning. Iwai’s Dancing Cleansing series (2010-15) takes on these formal qualities by treating the actions of cleaning as a performance. This kind of work is not without precedent, the most direct being perhaps Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Touch Sanitation: Follow in Your Footsteps (1977-80), which distilled the movements of New York City sanitation workers’ daily jobs into a series of non-utilitarian actions. Ukeles then expanded her study of movement to the actions of the sanitation machines themselves, re-choreographing them into a series of mechanical ballets (1983-2012) performed by local sanitation workers in parades and festivals in New York, Tokamachi and Rotterdam.

But whereas Ukeles’ performances, like many such “worker ballets,” generally focus on institutionalized movements and settings to seek a common, almost universalized language of movement, Iwai’s works lean toward a consideration of the personal, the habitual and the private. This is most obvious in his Tbilisi videos, in which participants combine cleaning actions with dance forms that seem to range from quasi-ballet to street dancing and folk dance. The personal idiosyncrasies of individual style sit in tension with the recognizable formal qualities of both dance forms and cleaning actions.

Such tensions reach a peak in Bon Dance—Akita (2015), a three-screen video that combines footage of traditional but no-longer-performed Bon dances from Akita Prefecture on the left screen; historical footage of periodic collective cleaning efforts around water sources in Akita on the right screen; and documentation of collective cleaning actions Iwai organized in 2015 around the few remaining unpolluted natural springs in the middle screen—a reminder of past habits that have given way to contemporary consumer lifestyles. The communal and collective nature of the historical Bon dances and cleaning activities are at once representative of local culture, forming a background for contemporary habits, but at the same time stand in opposition to the new, individualized, compartmentalized and de-localized habits of dishwashing, clothes cleaning and government sanitation systems that globalized consumer culture pushes us toward. The conflation of dance and cleaning, in this formation, then serves to question boundaries between domestic and public space, personal habit and commercial imperatives, local ritual and local environment.

In an area hit hard by the past half-century of urbanization and industrialization, further compounded by the effects of the 2011 earthquake on the Tohoku region (of which Akita, though not directly hit by the tsunami, is a part), this constellation of questions has an unsettling undertone. The centrality of local water sources to these images, in combination with the image of Bon (or Obon) as a time of calling the dead to the villages for ceremonies of recognition, seems to conjure the ghosts of the tsunami from neighboring prefectures. The mass processes of cleaning that took place along the eastern coasts of the nearby prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima in the wake of the tsunami were intimately tied to industrialization and commercial distribution systems: big-box consumer stores, manufacturing facilities and office blocks collected alongside shipyards in the lowland valleys swept away by the terrifying waves. The cleaning and seasonal rituals of the area rely on the cleansing power of water at the same time they are derived from the potential violence of its power. But as these local habits and rituals are replaced by “globalized” habits derived from capitalist consumer culture, the knowledge of local environment is also lost, hidden behind the apparent tabula rasa of “modernization.”

This potential danger and violence born of the conflation of modernization with hygiene and cleanliness returns again in Iwai’s works in Taiwan, a former colony of the pre-1945 Empire of Japan. The rhetoric of hygiene is commonly used to rationalize the expansion and violence of colonialist empires, as it was in Japan’s annexation of Taiwan. The foreign lands colonized are ostensibly “saved” by the colonizer through the imposition of new, modern lifestyles and urban structures billed as hygienic and efficient.

While not explicitly cited, it is difficult to imagine such histories are not invoked and complicated by the dirt accumulated on the Japanese and Taiwanese national flags used to clean the surfaces of an abandoned building in Iwai’s Flag Cleaning (2010), or by the alternatively mournful and contemplatively slow accumulation of suds on a neglected colonial-style Taiwanese structure in Old Japanese House—Intro (2010). Cleaning here seems to become a mode of exposing lasting tensions as at the same time the dynamic that places the colonizer in the role of modernizer appears inverted by the nostalgic, decrepit architectural settings of these videos.

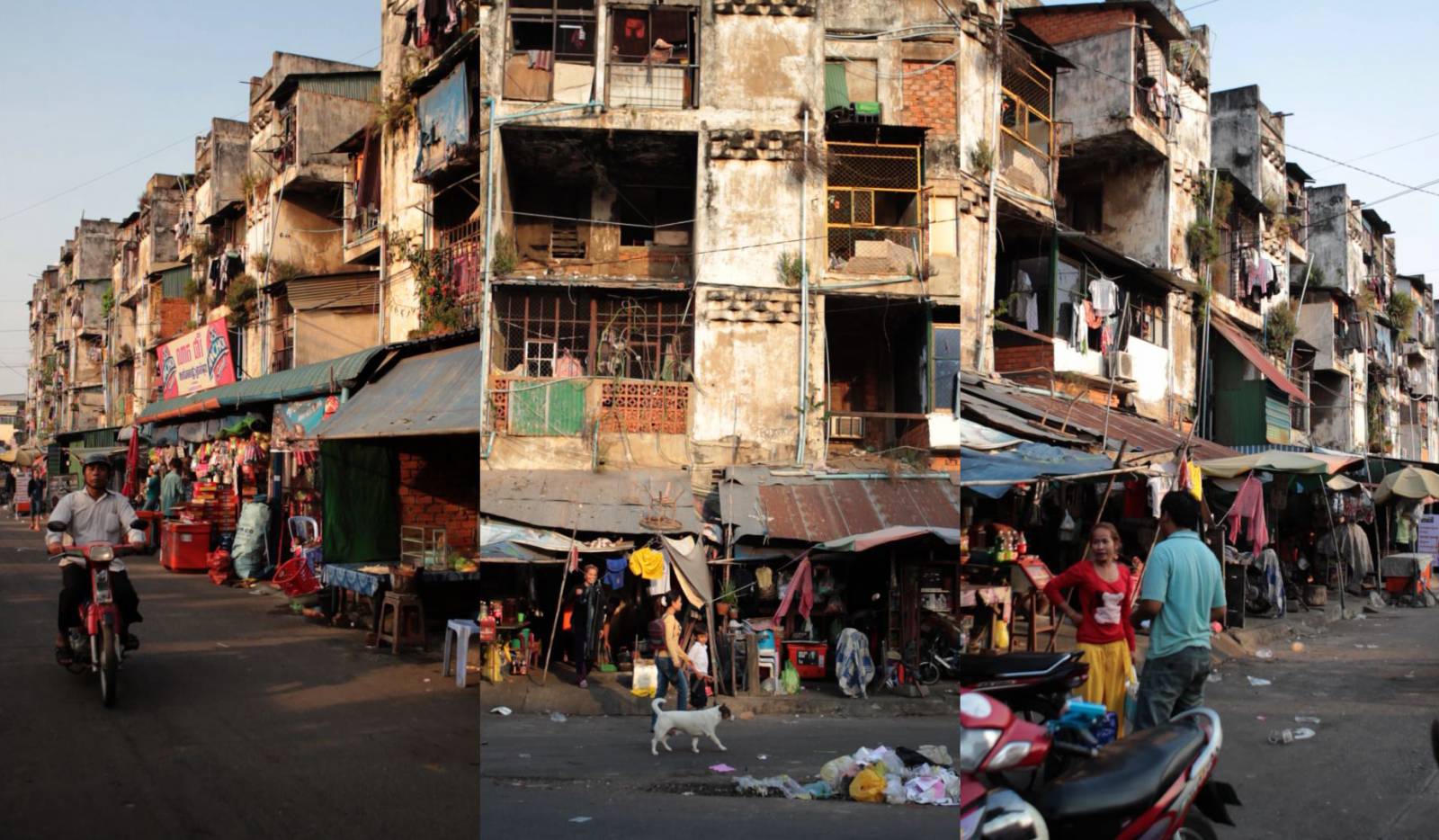

Yet it is not only through the colonialist dynamic that modernization and hygiene are implicated in the violence of hierarchical social structures. In post-World War II Cambodia, Phnom Penh experienced a dramatic population surge that led then-King Sihanouk to implement a modernization project. As a part of this plan, Cambodian architect Lu Ban Hap and French/Russian engineer Vladimir Bodiansky constructed, in 1963, a Le Corbusier-inspired, multi-story modernist building now known as the White Building: a municipal apartment structure to house middle- and lower-class Cambodians.

Like many other modernist housing projects across the world, however, planning for maintenance was minimal, and since the residents have been primarily composed of civil servants, street vendors, artists and craftsmen, cultural workers and social outcasts, there has been little political will to maintain or refurbish the building over the past half-century.[2] Now, on the eve of its destruction, it reads as a slum, with glimpses of its architectural bones peeking out from overgrown plants, accumulated grime, peeling paint and haphazardly accumulated awnings.[3] The interiors are dark, mostly lit by what little natural light filters in through the openings and perforations in the stairwells. Litter and dirt collect in the corners, and stains mark those walls that the light can reach. The units are in desperate need of repair, with some lacking running water or even exterior walls to provide shelter from the rain. What was once a modernist dream is now an agglomeration of the discarded; but at the same time, what little shelter it does provide is as much as most residents can afford, and the community assembled here cannot be reconstructed elsewhere in existing Phnom Penh. As the Japanese firm Arakawa prepares for demolition of the structure and construction of a new, 21-story luxury condominium building, the dynamics of hygiene and modernization are, ironically, invoked against a modernist structure to justify the displacement of marginalized communities through the intervention of an economic imperial power.[4]

Against this backdrop of a violent rhetoric of hygiene imposed from outside, Iwai’s White Building Washing (2012) shows us cleaning as a spontaneous and collective action by the community of local residents. The video brings us slowly into the rhythms of daily life here, beyond what we can see from the street, focusing on quotidian acts of organization and tidying—the collection and separation of bottles and cans, hand-washing of clothes in metal tubs, and ironing of clothing. Yet Iwai also reveals the accumulation of litter and grime with the help of a roving flashlight in the dim hallways.

Then the cleaning begins. The sweeping out of litter is followed by a flow of soapy water across hallways and stairs. Brooms, rags and brushes scrub at floors, railings, ceilings and walls. Children, adults and the elderly all join in, but with water spilling down several stories at the walkways between units, the process reads as more organic than systematic. Even if the action itself is staged, the methodology and the washing process Iwai presents seem derived from the fabric of the residential community, at odds with the systematicity and efficiency of capitalist hygiene. It is in this schism that we re-encounter Douglas’ dirt-as-disorder: is there an objective reason to prefer the Arakawa firm’s tabula-rasa “cleaning” of this “slum” over Iwai’s community washing the existing structure? Is this not, instead, a question of values and cultural practices? An example of the violence of classificatory schemas in collusion with the universalism advocated by global capitalism?

So where does this leave us in the end? Is it important that the context for Iwai’s work, as suggested by my initial comparisons of his oeuvre to Abstract Expressionism, takes place within the art context? In framing David Hammons’ work, writer and curator Tom Finkelpearl points out how the art institution, and its supposedly objective distance from the everyday, relies on the perceived “neutrality” of white people, white space, and “clean, white, middle-class values”:

Even the critique of the clean, white space—the traditional gallery or museum exhibition space—and clean white values is internal, and does not undermine the cleanliness of the art world … Who can guess from the look and feel of their [Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Barbara Kruger and Sherry Levine] art that they are working in a city that includes Bushwick, Harlem, Flatbush and Howard Beach?[5]

Finkelpearl argues against such sequestering in favor of art and exhibitions that include the messiness of the physical and social context of art making. He looks to art that seeks the crumminess of the streets, especially in the margins of urban space, in order to bring in the racial, social and economic issues that the “contrived dirt” of Abstract Expressionism glosses over in its preference for personal gesture over social positionality. This is where Iwai’s work, too, intervenes, helping lay bare the prejudices and blind spots in the art institution’s continued predilection for modernist values and visions. In questioning the processes, values and definitions of cleanliness and hygiene within the framework of art, he helps to unmask the social construction of hygiene and the violence of its structural order. Iwai unveils for us the violence of the exhibition space and its culpability in the capitalist hierarchies of value creation at the same time that he reveals it to be a reflection of the violence implicit in processes of cleaning in the world at large.

< Back to Text Index

[1] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (New York: Routledge, 2008), 2.

[2] Sa Sa Art Projects and Big Stories Co., “About the White Building,” White Building, accessed June 14, 2017, http://whitebuilding.org/en/page/about_the_white_building#endref3.

[3] As I write this essay in June 2017, the building is being evacuated to prepare for demolition. My descriptions of its interior and atmosphere are recollections from a visit to the site in December 2016.

[4] Tara Yarlagadda et. al., “360 video: This historic Cambodian building, set for demolition, is a city within a city,” PBS NewsHour, June 3, 2017, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/360-vide-white-building-cambodia-demolition/.

[5] Tom Finkelpearl, “On the Ideology of Dirt,” David Hammons: Rousing the Rubble (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), 66.